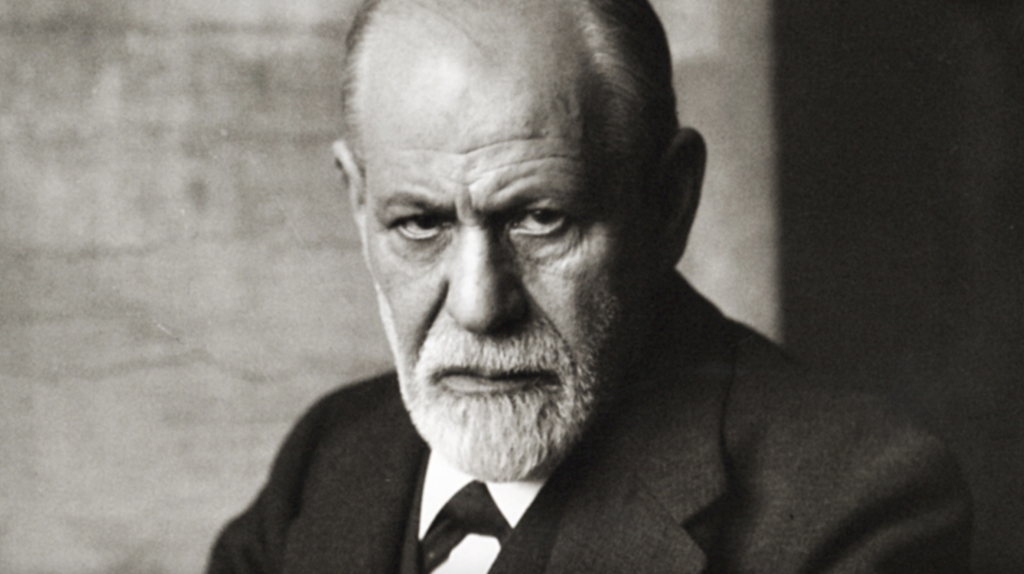

Now comes the reckoning! Now we shall enslave all these mediocre kitschmongers and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God.

This is how the modernist composer Arnold Schönberg expressed his enthusiasm for the breakout of the First World War in a letter in 1914 to his friend Alma Mahler. Those mentioned were his colleagues Bizet, Stravinsky and Ravel, who were admittedly on the opposite side of the war, but who had fallen out of favor for another reason.

It was German Idealism’s ideas of originality, disinterestedness, and the supersensible that were about to take over the culture of Western countries. The adventurous music of the bourgeoisie, which had developed in complexity since the 17th century, was about to implode. With Hegelian dialectics as a starting point, Mozart, Beethoven and Schumann were no longer to be considered as craftsmen, but as geniuses who, by virtue of their pioneering abilities, forced history to move forward. The future of music was to be fulfilled and this meant a hard break with what was considered decadent imitation. In its place, an intellectual music was to take over, devoid of melody and storytelling. Painting, sculpture and architecture were also to be subject to the same deconstructivist currents. The mainstays of the various disciplines were to be reassessed and replaced: the recognizable in the visual arts, the harmonious proportions in architecture, the melody in music. These tendencies were to be collectively called Modernism.

Modernism takes over

It can be difficult to imagine the challenges associated with composing tonally after the Second World War. Modernism, with its atonalism, had become dominant, and covered Europe like an iron curtain. The dissenters were ridiculed as late romantics, which ensured that many personalities ended up in the shadow of the time’s standard bearers of «true art». Gradually, it became difficult, indeed almost impossible, to be taken seriously as a melodious composer, because one was convinced that progress meant the abolition of tonality.

We would like to present a selection of composers who, despite the zeitgeist, have written classical music since the Second World War – up to the present day. The list is an attempt to collect the most excellent composers, who regularly wrote music that grips and engages.

Developing the list, we have settled on two criteria for what qualifies as "classical music":

1) The music must be varied tonally. If it seeks out too many dissonances, it turns to modernism, if the chromatic scale is employed too much, it becomes jazz. If it operates with too simple structures, it becomes indistinguishable from ballads or popular music.

2) It is a prerequisite that the composer has used acoustic instruments. Some recent film music can be said to be classical in form, but the use of synthesizers and digital soundscapes makes the music inorganic and unreproducible.

Note! In the list we highlight what we consider to be the composers' best works written after the Second World War. Those who were still alive but did not write in the given period, for example Sibelius, are not included. We have also avoided mentioning so-called one-hit wonders, because the list should function as an overview of the most knowledgeable composers, with the caveat that we may have overlooked names.

Wilhelm Furtwängler

Symphony No. 2 (1945-46)

Furtwängler is primarily known for recreating what many consider the ideal sound of Beethoven, Bruckner and Brahms in his role as a conductor. What most people do not know is that he primarily defined himself as a composer.

The highlight of his work is Symphony No. 2, written in Germany in 1945. He had conducted under Hitler and was therefore investigated by the Allies. The heavy atmosphere that characterizes the soundscape is reminiscent of his role models such as Anton Bruckner, although the notion of gloom and doom is a general tendency in 20th-century music. The symphony opens with a surprising and chromatic bassoon motif, which is gradually accompanied by romantic strings that bring the melody into tonality. The play between chromatic and romantic motifs is recurring throughout the work, and ends with a dramatic fanfare, as if proclaiming that it was one of the great romantic symphonies.

In retrospect, his compositions represent a wholehearted attempt to venerate the old masters, and his role as a conductor undoubtedly seems to have benefited from this endeavor. With the compositional interest in mind, he was able to supply Brahms, Schubert and Beethoven the enthusiasm and energy their works deserve. Unfortunately, the conductors of the succeeding generation stopped composing, and their approach to the classics have since been more about style than storytelling.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Cello Concerto Op. 37 (1946)

The Austrian composer was a rare instant of a child prodigy in the 20th century. In his teens he wrote chamber works, ballets and his first opera. Gustav Mahler praised the aspiring composer and with the subsequent operas, even Richard Strauss and Giacomo Puccini celebrated him. Composing The Dead City (1920), in which the Puccini-sweet aria Marietta’s song is worth highlighting, he distinguished himself as a late romantic.

When the persecution of Jews by the National Socialists was set in motion in Germany in the 1930s, he made the fateful choice to accept the invitation to move to the United States to compose film music for Max Reinhardt. This was to be the beginning of a new career: instead of operas and piano trios, the Austrian was to make a living by scoring adventure movies and film noir thrillers in Hollywood.

With his classical background, Korngold was loved by the film industry and the entertainment industry embraced his melodic urge. Together with Max Steiner, Korngold is considered the founder of film music. His expressive and vital violin concerto was originally written for Deception, starring Paul Henreid as a composer in love. When the film was completed, Korngold rewrote and extended the piece and gave it a separate opus number. The cello concerto, as well as the romance from his violin concerto (1945) and the adagio from his symphony (1952), represent a romantic depth that the modernists falsely had declared as extinct.

Nikolai Myaskovsky

Symphony no. 25 (1946)

Hearing Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony in 1896, Nikolaj Myaskovsky decided to become a composer. He was a late bloomer, but gained a friendship for life in his younger, fellow student Sergei Prokofiev during his studies in St. Petersburg.

Midway in his career, Myaskovsky had an experimental period, but was otherwise the entire «conscience of Russian music», as described by biographer Gregor Tassie. Symphony No. 25 is a testament to his refined orchestration abilities and has an opening motif which could be described as transcendent or otherworldly. There is something intimate about the music, which can also be heard in the second movement of his optimistic last symphony. Critics in the Soviet Union remained skeptical, accusing him of writing music inspired by his own feelings rather than those of the proletariat. The composer on his part was a shy, reclusive man, and despite all the public accusations, he retained his professorship at the Moscow Conservatory until death in 1950.

Conductor Yevgenij Svetlanov was an active promoter of bringing Myaskovsky’s symphonies back to light, where The Aviation Symphony is worthy of special attention. Svetlanov has drawn parallels to Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner, both of whom experienced a renaissance long after their passing.

Richard Strauss

Four Last Songs (1948)

The leading star Richard Strauss emerged as a Wagnerian modernist in his youth, but would spend his adult years in the dream world of kitsch. He is best known for the comedy opera The Rose Cavalier and the symphonic poem Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

In Four Last Songs, the Viennese composer strikes a final romantic chord in four movements, with the last being especially noteworthy. Im Abendrot is about an old married couple who mournfully but composedly wander into the sunset as they ask themselves: «Could this be death?»

The song is partly reminiscent of his opera Arabella and ends with the unforgettable clarinet tones that must be said to be the passing tones of a dying man.

Hans Pfitzner

Cantata after Goethe’s Urworte Orphisch (1948-49)

After the war and the Allied bombing raids, the German composer Hans Pfitzner was homeless and mentally impaired. Before he died in a retirement home in Salzburg, he composed the cantata Urworte Orphisch based on a poem by Goethe. The piece is dramatic and akin to the Requiem by Johannes Brahms.

As an outspoken anti-modernist, in addition to being a critic of Nazism during the war, Pfitzner encountered a lot of opposition. The National Socialists considered his old-fashioned music unsuitable for propaganda and posterity has given him little credit, simply because he was a performing composer in Hitler’s Germany.

Among his other works, Pfitzner’s romantic cantata Von Deutscher Seele is highly recommended.

Rued Langaard

From the Deep (1950-52)

The composer Rued Langaard was ostracized early on from the music circles in Denmark. He starved and froze because no one would give him a permanent position as an organist. After applying for more than twenty years, he was «exiled» to the cathedral in Ribe with a very low wage. In 1952 he revised the choral work From the Deep, which was to be his last before he died, completely unrecognized.

At the end of the 1960s, however, Langaard began to emerge from Carl Nielsen’s all-encompassing shadow. This is largely due to Per Nørgård, who smuggled his Music of the Spheres in-between new works that were to be assessed by a modernist committee for the Nordic Music Days festival.

But Langaard was no modernist. His music is pompous and wondrous. Sometimes it is almost as if he lets the listener peek into a realm of burning anxiety. His Fall of the Leaf symphony ought to be familiar to every listener.

Sergei Prokofiev

Symphony no. 7 “Children’s Symphony” (1952)

Was Sergei Prokofiev a modernist or a late romantic? The question has divided many, and although there is no doubt he experimented a great deal in his work, he can also be strikingly sentimental.

In the post-war years, his very last and 7th symphony, is a beacon of light. As with several of his works, chaos reigns, but the adventurous motifs in the first movement carry rivers of beauty through all four movements. The title «Children’s Symphony» expresses its melancholic outlook on life, but perhaps it is also reflective of a musical era that had moved away from the childish and melodic to the excessively intellectual.

When Stalin passed away on the 5th of March in 1953, Prokofiev was at his last, and it is said that the composer died of euphoria when he heard of the general secretary’s death. Among other things, he left the world having composed the ballet Romeo and Juliet, the music for the film about Alexander Nevsky and a wonderful third movement from Symphony No. 5.

Charles Chaplin

The movie Limelight (1952)

Chaplin is perhaps the only one among the giants who wrote, directed, composed and starred in the films he produced. The fact that he could not read sheet music did not prevent him from realizing his abilities in this field as well, with help from skilful musicians.

The music for the feature film Limelight is intimate and melodic to its fingertips. Parts were composed in advance to adapt the choreography of the ballet scene, which originally lasted nearly half an hour. For the orchestration, Chaplin was assisted by Ray Rasch and Russel Garcia. One of the themes was later turned into the popular song «Forever» with lyrics by Geoff Parsons and John Turner.

Other significant works by Chaplin are the music he scored for The Kid, City Lights, and Modern Times.

Edmund Rubbra

Symphony No. 6 (1953-54)

He has become known as the British Bruckner, as evidenced by the vitality and optimism of the finale of his Symphony No. 4. But the similarity stops there, because Edmund Rubbra was rather experimental in structure and tonality. While composing, he would often start with one melody, and then let the music flow intuitively like a lyric poet who writes in rhyme without metric structure. His impressionistic approach may well have been a result of being a pupil of Gustav Holst, whose frivolous methods must have made a strong impression on the teenager.

Symphony No. 6 is often highlighted as Rubbra’s major work, and was written when he was at the height of his social standing. The adagio is fabulous, and can occasionally remind one of a similar movement from Vaughan Williams’ London Symphony.

The dedicated conductor Richard Hickox deserves applause and honor for his work in performing Edmund Rubbra’s combined eleven symphonies, which deserve more attention than they have received in recent times.

Aram Khatchaturian

The ballet Spartacus (1954)

Some pieces of music have something immediately recognizable about them. An example of this is the Adagio for Phrygia from the ballet Spartacus. Already after listening to the first notes, one thinks: where have I heard this before? The shock of discovering that this tune originates from a ballet written in the 1950s cannot be described in words. The Armenian Khachaturian is unknown to most people, yet he had the ability to make melodies that you will never forget. Another example is Sabre Dance from his ballet Gayané (1939).

Spartacus remains his most epic work. The ballet tells the true story of the Roman gladiator Spartacus and his slave rebellion around 100 years before Christ. The mix of choirs in the music is effective and gives us a small glimpse of antiquity. The music is crudely melodic, a special case in its era. This ballet deserves respect on a par with The Nutcracker by Tchaikovsky.

Nikolai Kryukov

The movie The Forty-First (1956)

As perhaps the foremost film composer in the Soviet Union, it is really surprising that his name is not preserved in the consciousness of musicologists. Nikolai Kryukov was the musical director of Mosfilm and gave music to Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), The Idiot (1958), Admiral Nakhimov (1947), and several symphonies. If you look up his name on the internet today, you will first of all be bombarded with information about a gymnast and Olympic champion with the same name, then an actor. The composer, on the other hand, has been pushed under the relentless rag rug of history.

The Forty-First, directed by the legendary Grigoriy Tchukhrai,and made in the wake of Stalin’s death, is something unique as a film critical of Bolshevism. It takes place during the civil war in Russia in 1919, telling the story of a woman and a man who fall in love with each other despite war and ideological barriers. For Kryukov, this is his most sublime work as a film composer.

The combination of strings and longing soprano voices is a signature of Kryukov, who ended his life by throwing himself in front of a train on 4th of April, 1961.

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Symphony No. 9 (1957)

Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis has become part of the music canon, but Vaughan Williams is still an unknown name to many. This is mainly because his last symphony was published at a time when new romantic music was hardly known outside of Hollywood. However, «romantic» is perhaps not the best term to describe Symphony No. 9. The piece opens dramatically, with the faith of Saint Matthew Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach, and is partly based on the novel Tess of the D’Urberville Family by Thomas Hardy.

At the top of Vaughan Williams’ oeuvre reigns A London Symphony (1913), with its mysterious atmosphere and rich tonality, masterfully conducted by both Richard Hickox and John Barbirolli.

During his studies, Vaughan Williams was a student of both Max Bruch and Maurice Ravel. The person closest to him was Gustav Holst. They mutually considered each other to be their most important source of inspiration.

Dmitri Shostakovitch

Symphony No. 11 (1957)

Symphony No. 11 by Dmitri Shostakovich opens with an adagio that sets the tone for the winter morning known as “Bloody Sunday” in 1905 when the workers marched in protest and several were massacred by the imperial guard. The warlike use of timpani and trumpets in the second movement depicts the clashes that took place and here Shostakovich uses elements from one of his earlier choral works. Several melodies in the symphony are taken from folk tunes and revolutionary songs. The result is a masterpiece which, in the third movement, serves the listener one of the highlights in the history of music.

During his life, the Russian composer struggled a lot with his nerves. At times he had a pre-packed suitcase ready by the exit door and slept on a mattress in the stairwell for the sake of the family in case the KGB came to arrest him at night.

Shostakovich has been called the greatest symphonist of the 21st century, and for good reason. Prominent works are his fifth and eighth Symphonies, the film score for Grigori Kozintsev’s Hamlet, and his second piano concerto.

Francis Poulenc

The opera Dialogues of the Carmelites (1957)

Just when the musical had certainly replaced the opera genre for good, this classical opera turned up from a composer who is rather unknown today. Melodic from the first stanza, it proves to everyone that the classical idiom is not time dependent, but can reappear when you least expect it. His Stabat Mater is also a good example of this.

Francis Poulenc was a self-proclaimed classicist at a time when almost no one else dared to be. Together with five colleagues, he started a group with the nickname «Les Six». They wanted to make pure music, free of Wagnerianism and impressionism.

The opera Dialogues of the Carmelites tells of two choices and two tragedies. The first is about Cosette’s struggle with mysterious, soulful anguish. She finally leaves her childhood home to enter a convent. Her second fateful choice takes place during the French Revolution in the nunnery when Cosette and the other nuns decide to sacrifice their lives for the faith

Originality and forgery

If you have a poetic disposition, it is easy to romanticize the past. You hear something beautiful and immediately think it is old. This is not surprising, as time has a censoring quality. In retrospect, the ugly and uninteresting is often weeded out so that we are left with a glossy picture of the past.

In some disciplines, however, the sad truth is that something essential has been lost. The pioneers of modernism were classically educated, but the next generation was not so lucky. When the ‘60s knocked on the door in Western countries, the young composers were at a loss. There was nothing to build on. The past seemed even more enigmatic, with its secrets shrouded in a mythic veil. The new generation’s composers therefore searched independently in the treasure chest of history for inspiration.

It was a chaotic time when composers lived strange double lives: as classical musicians for the cinema screen, and modernists for the orchestra hall. When they wrote classical orchestral music, it was sometimes published under historical names that could justify the tonality of the piece.

In the East, the situation was quite the opposite. There, social realism was the prevailing form of expression, and tonality eventually became an absolute requirement. The fashionable, atonal music in the West infected a large number of Soviet composers, who would eventually find themselves operating with more dissonances than consonances. This tendency was broadly condemned as «formalism» and was severely cracked down on. An official decree in 1948, dubbed the Zhdanov Doctrine, declared Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Myaskovsky, Vainberg and Katchaturian, among others, enemies of the people, because they wrote music that went against Soviet ideals. Towards the end of Stalin’s reign, it was dangerous to be a performing composer in the Soviet Union and Shostakovich felt compelled to write the work of reconciliation Song of the Forests for Stalin’s 70th birthday. The piece fulfilled Zhdanovism’s requirements for melodiousness and harmony and even won the Stalin Prize.

In retrospect, it is easy to see the brutality and unreasonableness of Zhdanovism, but it is also understandable that the Soviets saw the need to limit modernist tendencies, which were in the process of destroying Russian culture from within.

Mikhail Ziv

The movie Ballad of a soldier (1959)

Mikhail Ziv received his music education at the conservatory in Moscow, and began to make his mark as a film composer in the 1950s.

Already in School of Courage (1954) one can hear the echo of the notes that he grinded into a diamond in Chukhrai’s masterpiece Ballad of a Soldier.

«Strangely enough,» wrote Ziv, «it is Grigori Chukhrai who is my teacher in film music. Without a musical education, he is able to inspire the composer in the most subtle way without resorting to musicological terms, contenting himself with gestures, shouting, and hints.”

Ziv and Chukhrai collaborated on several films, where Clear Skies (1961) and Untypical Story (1979) are also wonderfully set to music.

Nino Rota

The movie The Leopard (1963)

Some composers are lucky to find a form that fits like a hand in a glove. Nino Rota was a child prodigy like Korngold, but unlike Korngold, the Milano-born composer had a talent for simple and well-articulated melodies, which was appreciated in the film industry.

Posterity remembers him primarily for the film score for Godfather (1972). A lesser-known, but absolute highlight from his hand is the music for the film The Leopard, which deals with Italy’s transition from estate society to a republic in the 19th century. The main theme from The Leopard is wistful and nostalgic, just as the main character himself sees the old world falling apart.

Film director Federico Fellini once said that his best collaborator throughout his career had been Nino Rota. The composer apparently had a special ability for coming up with the right notes, not from seeing the motion picture, but entirely on his own after hearing the story. When he died in 1979, he had composed three operas, several symphonies and dozens of film scores.

Bernard Hermann

The movie Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

«I have the final say, or I don’t do the music!» These are the infamous words of Bernard Hermann, who believed most film directors were musically uncultivated. With Russian-Jewish heritage, he grew up in New York during the Prohibition Era and made his debut as a film composer with Citizen Kane (1941) by Orson Welles.

Hermann emphasized the importance of music being able to live on its own beyond cinema, and his work with Fahrenheit 451 has undoubtedly stood the test of time. The Finale is one of the most beautiful pieces written for film and will strike a chord with anyone familiar with Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings.

The music Hermann composed is anything but pompous. It often seeks disharmonies, and can become quite «chippy», but never stepping over into a modernist hotchpotch. He often operates with a small selection of instruments, and is best known for his collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock on the film Psycho.

Allan Pettersson

Symphony no. 7 (1966-67)

Unlike his colleague Lars-Erik Larsson, Gustaf Allan Pettersson never wrote that one-hit-wonder played repeatedly on all the radio stations, but who knows, it might still happen and then his Seventh Symphony is a solid candidate. In addition to being wonderfully melodic, the piece has a long and dramatic build-up to a crescendo of stuttering strings that send chills down one’s spine. The symphony evokes so many emotions in the listener, that after being fully immersed with it a few times over, one can be nothing less than inspired to become a better person.

Pettersson composed a total of seventeen symphonies and almost exclusively in one movement, which gives the music a strengthened sense of totality. They can be noisy and many lack tonality, but his Eighth and Ninth symphonies are pieces worthy of consideration.

Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov

Elegy in Memory of Rachmaninoff (1973)

The young talent Ovtchinnikov was declared by Shostakovich to be the most prominent composer of his generation. He wrote two symphonies before the age of twenty, scored the seven-hour long film War and Peace (1968), as well composing music for a number of old silent films. In the ‘70s, he picked up the conductor’s baton, thus following in Furtwängler’s faded footsteps as a composing conductor. With the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra on Rakhmaninov’s centenary, he premiered his own elegy in memory of the late composer. The piece, with its masterful depth of orchestration, combined with traditional Russian folk tunes, has since been a favorite among Muscovite audiences.

The listener who wants to get to know Ovtchinnikov’s music better should listen to the masculine A Space Symphony (1952). In it, the strings howl and screech completely unrestrained with rare vitality, resulting in speculation as to whether it inspired Allan Pettersson when he wrote his seventh symphony ten years later.

Georgy Sviridov

Snowstorm-Suite (1974)

This is one of the many hidden gems of Russian culture. Rarely has a collection of pieces of music been of such an unforgettable character as the Snowstorm Suite by the Soviet composer Georgy Vasilyevich Sviridov. Here, you are unashamedly served one whistle-friendly line of notes after another, and you ask yourself each time: «haven’t I heard this melody before?» It is almost strange that this master of tonality, who was a contemporary of Shostakovich, is not better known.

The suite is based on Sviridov’s music for a film adaptation of Aleksandr Pushkin’s short story of the same title. His choral work Reveille is also highly recommended.

Franco Mannino

The movie Innocence (1976)

Franco Mannino was an Italian pianist, conductor, choreographer and composer with a versatile repertoire. It is rare to come across people from the 21st century who have composed both symphonies and operas.

He is best known as a film composer. He held Nino Rota in high esteem and believed that the film required an equally humble tunesmith. When he finally married the sister of the director Luchino Visconti, the stars aligned for an immortal collaboration. His score for Innocence is among the most melancholic written for cinema.

Mannino once said that film as a medium would lose at least half of its impact without music. This must be said to be the case in Visconti’s film, where the quivering violin strings supplement the underlying drama of the story.

Mannino’s music is sometimes very romantic and the composer does not hide his sources of inspiration, be it Johannes Brahms or Pietro Mascagni. His Violin Concerto No. 2 and the Panormus Symphony are so hauntingly beautiful that you will have a hard time not remembering them.

Liberation with Postmodernism

Even the finest were infected with the bubonic modernist plague. Composers such as Allan Pettersson, Ennio Morricone, John Tavener and John Williams have occasionally made things that can hardly be described as anything other than tone-deaf nonsense. It is reasonable to believe that several Western composers limited their own tonality, not for the sake of expression, but simply to have their music performed.

But in the late 1970s the Avant-garde movement began to lose its firm grip on high society. A group of French philosophers had received attention for their criticism of power structures, with the leading idea that there is no objective truth. This meant that modernism, which started as a skeptical project and later became dogmatic, was put into question. «Everything should serve progress» was thus replaced by the mantra «everything is allowed».

Paradoxically, this sparked a redemption for the rule-oriented, classical form, and facilitated a careful opening up to performing new classical music in the orchestra halls. Quite a few who had previously dabbled with atonality were radically transformed as composers. This was especially true in the Baltics.

But it was not the structured Brahms or the chaotic Wagner that formed the basis of postmodern music. The 1980s became the decade of minimalism, an attempt to catalyze a primitive rebirth of the classical form through pure and meditative music. It is characterized by frequent use of vocals and is related to Renaissance music.

Postmodernism was decisive for several unknown composers who have since been among the most influential in the 21st century.

Henryk Górecki

Song of Sorrows (1977)

Gorecki’s third symphony is about motherhood and grieving women, but it also represents a decisive turn for the Polish composer, who had started out as an ordinary formalist. With the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, Gorecki stepped into minimalism and tonality, ensuring for the symphony popularity of a rare kind for classical music. He is still considered the greatest commercial success among modern symphonists, although he has not gained significant attention for his other works.

Gorecki lost his mother when he was two years old and was plagued with illness much of his life. «I talked with death often», he said on one occasion. He was working on his fourth symphony when he passed away in 2010. It was completed by his son Mikolaj, who is also a composer.

Echoes from Gorecki’s Third can be heard in the second movement from his preceding Symphony No. 2, which also has great qualities.

Arvo Pärt

Fratres (1977)

The young generation of listeners will likely draw lines to Max Richter when they hear Arvo Pärt’s Fratres for the first time. Some have probably also noticed that the piece is used in the film There will be Blood by Paul Thomas Anderson.

Pärt was not particularly well-known outside Estonia’s borders until he orientated himself away from the atonal and became a minimalist in the late 1970s. Fratres (meaning Brothers) was among the first pieces he wrote in the so-called tintinnabuli style. During the work with Fratres, Pärt said that «the instant and eternity are struggling within us… this is the cause of all our contradictions.»

He is also known for Spiegel im spiegel, but is particularly distinguished by his Lamentate for piano and orchestra.

Krzysztof Penderecki

Christmas Symphony (1979-80)

If you want to get into the Christmas spirit, it’s time to get to know the Polish composer Penderecki and his second symphony, where the first notes from Silent Night are used multiple times. The Christmas Symphony is insidious like a stormy winter night, but takes the listener on a journey through sublime moments of redemption.

According to his own statement, Penderecki began his musical career as an angry young man, and he was known as a leading avant-gardist in Poland. In the 1970s he turned critical to twelve-tone music and switched to the use of semitones and the devil’s interval, before gradually embracing the classical form with his first violin concerto.

«The avant garde gave the illusion of universal validity,» he later stated, concluding that formalism was rather destructive.

Penderecki’s music is temperamental and gloomy. It is therefore no surprise that it has been borrowed in several horror and mystery films. Notable is the Passacaglia movement from his Symphony No. 3, which is frequently used in Martin Scorcese’s Shutter Island.

Ennio Morricone

The movie Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

It can be overwhelming to shuffle through Ennio Morricone’s vast production, which does not run short of highlights. His collaboration with director Sergio Leone is among the most successful in the history of film, and fascinating in more than one way. For the movie Once Upon a Time in America, he had composed all the themes almost ten years in advance, and while shooting the film, Leone ensured that the music was performed to set the mood for the camera operator.

Morricone is a master at promoting feelings of nostalgia, regret, and melancholic reminiscence over a life lived. In addition to classical instruments, he often makes use of harmonica, whistling and various woodwinds. Other movie scores to recommend are Once Upon a Time in the West, Cinema Paradiso and The Best Offer.

Jean-Claude Petit

Jean de Florette & Manon and the Spring (1986)

Claude Berri’s masterpiece Jean de Florette and Manon and the Spring have become known as «Oedipus in Provence». The films, which were based on the two-volume novel by Marcel Pagnol, reintroduced French cinema to an international audience, and were also Jean-Claude Petit’s breakthrough as a composer.

Little did people know that he had already scored a number of films under another man’s name. In the 1970s, the modernist composer Michel Magne employed several young talents, including Petit, to ghostwrite movie soundtracks.

In Jean de Florette, Petit finally emerged from Michel Magne’s shadow and put together a memorable album of countless variations on a theme from Guiseppe Verdi’s opera The Force of Destiny. The striking feature of his music is the combination of his academic perfection and the fact that he does not hold back his sentimental inclinations.

Petit later wrote music for movies such as Cyrano de Bergerac (1990) and Les Miserables (2000).

Moisei Vainberg

Symphony no. 21 (1991)

Vainberg received his musical education in Warsaw, but fled to Belarus when the Germans occupied Poland in 1940. His sister, mother and father were interned in the Łódź ghetto, and later met death in the Trawniki concentration camp.

When the war came to the Soviet Union, Vajnberg was evacuated to Tashkent in Uzbekistan, where he met his future wife and Shostakovich, who persuaded him to settle in Moscow.

For a period his music was banned as a result of the Zhdanov doctrine and he made a living by composing music for circus and theater. In 1948, his father-in-law was liquidated by the authorities and Vainberg himself was arrested five years later, suspected of having participated in a Jewish-bourgeois conspiracy. With the help of Shostakovich, he was released after Stalin’s death.

As a composer, Vainberg is uneven, but in return he conjures up transcendent moments, for example in the wedding scene from The Cranes are Flying and the adagio from his twelfth symphony. His twenty-first and very last symphony is a heartbreaking tribute to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto. Never to see his childhood town again, he died in 1996.

The premiere of his opera The Passenger at the Bregenz Festival in 2010 was a great success and Vainberg is about to receive the recognition he never enjoyed in his lifetime.

Zbigniew Preisner

The movie The Double Life of Veronique (1991)

Zbigniew Preisner has not been fairly recognized for his work as a composer. He is primarily known for his collaboration with the film director Kieślowski on the Three Colors trilogy and The Double Life of Veronique (1991). It is precisely the music which he composed for the latter that has the potential to conserve the name “Preisner” for posterity.

The special orchestration in Preisner’s music can be explained by the fact that in his twenties he trained himself to become a composer by listening to vinyl records. Since then, he has scored a long list of films and, among other things, written an extensive requiem.

John Tavener

Song for Athena (1993)

Early on, John Tavener was inspired by Stravinsky and began his musical career as a noisy composer. In the 1970s he discovered Russian Orthodox Christianity and became deeply religious. His subsequent works were given a simplified, tonal language, known as «sacred minimalism».

A choral work he later composed is Song for Athena. Most people associate this piece with Princess Diana’s funeral, where it was performed during the coffin procession in Westminster Abbey. The fact that this choral piece was performed in honor of the pop icon Diana, and not Queen Elizabeth, is truly a mystery. A more unforgettable farewell ceremony will perhaps not be seen in our lifetime.

It is said that Tavener could go for months on end with the music carved out in his mind before he wrote it down without making a single correction. The commission Fragments of a prayer for the movie Children of Men is also highly recommended.

John Williams

The movie Schindler’s List (1993)

Since its inception, film music has been colored by giants who have defined the sound and temperament of the genre. Max Steiner’s and Korngold’s classicist approaches, guided Hollywood’s in its infancy. Nino Rota and Ennio Morricone dominated the latter half of the 20th century, and Hans Zimmer has been defining for the current era.

Between Zimmer and the classics, John Williams stands as a stalwart, or more precisely as the potato of film music. Being skilled, reliable and diverse in his abilities, he was an absolute favorite among directors in his heyday. In that sense, it is no wonder that he has the most Oscar nominations on record.

Schindler’s List is a moving film, but would it have been the same without Williams’ music? Basing the main theme on an old Jewish folk tune, he employed strings, bassoons and flutes on a classical journey that alone can make the audience cry.

Timothy Brock

The movie Faust (1995)

Rarely has a composer done more for silent films than the American Timothy Brock. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis are two examples, but the shining diamond is his music for Murnau’s Faust. The fact that Timothy Brock is not a well-known composer is difficult to understand. It was in 1995 that he faithfully scored the music for Faust, a soundtrack which is so rich in variety and drama that it should have been performed often, with pomp and splendor in the world’s orchestra halls.

If you want to see Brock’s performances or hear his music, there is no shortage of opportunities. In addition to constant tours in Europe, he has composed music for a total of 27 silent films during his career, in addition to having restored countless others.

Philip Glass

The movie Kundun (1997)

The strange thing about Philip Glass is that you can listen to his music for a long time before you realize that he is repeating the same notes over and over. Glass is the master of minimalism and has written several symphonies, but is probably most prominent as an opera composer. Satyagraha is worth noting as peculiar and hypnotically beautiful.

His lyrical and romantic music culminated towards the end of the 1990s, when he scored the music for Martin Scorsese’s film about the life of the fourteenth Dalai Lama. Grounded in classical orchestration, Glass eminently combines minimalism with Tibetan instruments, vocals and throat singing. The Kundun movie soundtrack belongs to the best written in the genre and is heavily underrated.

Glass later wrote his Second Violin Concerto, which is also an exquisite work.

Karl Jenkins

The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace (1999)

The Welshman Karl Jenkins is perceived by many as a postmodern composer, largely because his sources of inspiration are not limited to European music. But the expression is classical, as evidenced in works such as his Palladio for string orchestra, which is hard to erase from one’s mind once listened to.

The Armed Man is perhaps the best example of Jenkins’ broad horizon, particularly the third movement: «Kyrie». It has the appearance of being archaic, as if it could have been written by Tomas Luis de Victoria in the 17th century. The sadness it expresses is perhaps not particularly European, nor rooted in an era, but rather timeless and nationless.

Hans Zimmer

The movie Gladiator (2000)

The rock star of classical music is, without a doubt, Hans Zimmer, who more than anyone else has defined film music of the 21st century. With good reason, because his way of composing is captivating, to say the least. If John Williams is the king of recognizable melodies, Hans Zimmer is the master of rhythm and drama. Where others have the orchestra hammer away at their instruments, Zimmer gets close to the performers and captures the texture of the violin strings, making any cinemagoer hold on to their chair for dear life.

Zimmer has not been alien to synthesizers and unconventional instruments in his work. At the beginning of the 2000s, he still had what could be said to be a strictly classical period. The music of the blockbuster Gladiator pairs the story of Maximus Severus as masterfully as it is directed by Ridley Scott, and is a work that will be sung by posterity.

In recent years, Zimmer has adopted less and less classical instrumentation. Despite this tendency; he continues to deliver some of the most defining music in Hollywood.

Bruno Coulais

The movie The Chorus (2004)

The combination of unrestrained tonality and the absence of cheap tricks is a rare commodity these days. It often happens that the composer finds a combination of appealing chords, and then resorts to the same recipe each time instead of coming up with a musical theme and virtuously exploring its possibilities. This rare combination has a name in France and that is Bruno Coulais. The Paris-born composer was schooled early on at the piano and violin before he effortlessly slipped into the world of film music.

In The Chorus it is difficult to separate the music from the images, and Coulai’s contribution received at least as much attention as the movie itself when it was released. The recognizable melodies performed by orchestra, boys’ choir and piano, stole the hearts of everyone who heard them for the first time. They are so immediately beautiful that one automatically assumes they must be old folk songs. A highlight is the song Caresse sur l’ocean, and its exquisite, interwoven harmonies which can make even the most die-hard person cry.

Among other works by Coulais, The Count of Monte Cristo (1998) and Himalaya (1999) are much recommended.

Jean-Charles Gandrille

Stabat mater Litany (2015)

For many, the discovery of this young French organist was a stroke of bad and good luck all at the same time. In the wake of the fire in Notre-Dame in 2019, attention was given to the litany for organ and soprano, performed in the cathedral on Palm Sunday the day before the disaster.

In Jean-Charles Gandrille’s music, one can hear the echo of Arvo Pärt and Gabriel Faurè. His wonderful Stabat Mater is as good as a meeting between the two, where minimalism is united with the pale melancholy of the sacred voices. Even more minimalism can be heard in Variations for violin and organ, which is also an excellent work.

If you wish to hear Gandrille perform live, you can seek him out in the St. Lubin church in Rambouillet or Notre Dame in Auvers-sur-Oise just outside Paris.

Martin Romberg

The violin concerto Poemata Minora (2015)

The foremost among the living composers in Norwegian context seems to be Martin Romberg. He has given modern myths life through symphonic poems and piano pieces. Among his most prominent works is the violin concerto Poemata Minora, inspired by the poetry of H. P. Lovecraft. The second movement is particularly beautiful. Hearing Catharina Chen on violin as the movement reached its crescendo can send chills down one’s spine.

Romberg’s music is surprising and often finds its way into J.R.R. Tolkien’s universe, including the symphonic poem Quendi.

Alexander Blechinger

Atomblitz-overture (2016)

Being a music student in Vienna in the 1970s must be the equivalent of winding up as a bone-dry modernist. However, this does not apply to the Austrian composer Alexander Blechinger, who has actively fought for the betterment of melodious music.

In 1982, he founded the association and record company Harmonia Classica, which aims to perform beautiful, classical works by living composers. The association has regularly organized competitions over the years and released dozens of CDs with new music.

One of the highlights of Blechinger’ own production is his Atomblitz-overture. The theme is so unforgettably beautiful that it shines as a testimonium to his importance as a composer. It premiered in 2016 as a prelude to Simä, which is an intended opera about two unrequited lovers who find themselves in the middle of a nuclear war.

Blechinger belongs to the category of composers who adhere strictly to the conservative form, to which he has granted elegies, oratorios, duets and much more.

Frederik Magle

The Secret Garden (2019)

The child prodigy Frederik Magle from Denmark is considered by some to be a composer of “contemporary music”, but his approach is rather classical and kitschy in the most positive sense of the word.

The Secret Garden (2019) was commissioned for a hospital for elderly people, but it could just as well have been written for a feature film with the same title.

Like Gandrille, Magle is an organist and has composed two organ symphonies. He has also established himself as a film composer, a development that will be interesting to follow in the years to come.

Alma Deutscher

The Waltz of Sirens (2019)

She has already written an opera, concertos for both violin and piano, and is not yet twenty years old! The child prodigy Alma Deutscher from England has been called the 21st century’s Mozart, but far from a modernist one. Her music is unconditionally melodic and she manages to combine a wide range of instruments with varied tonality. It is therefore not surprising that she was boycotted by the music press when her major works were performed at Carnegie Hall in New York a couple of years ago.

«If the world is so ugly, what’s the point of making it even uglier with ugly music?» This is how Deutscher responds to the critics, who are impatiently waiting for her to find her «own voice».

In The Waltz of the Sirens she has tried to get beautiful notes out of the noise of the modern world. The music is related to Schumann, Chopin, Rickhard Strauss, in short, she sends the listener back to Vienna’s heyday 150 years ago, but more importantly: She revitalizes the tradition.

The future of classical music

Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.

(Ascribed to Gustav Mahler, but really a paraphrase of a text by Jean Jaurès)

In modern times, contemporary classical music has not had access to the orchestra halls to any significant extent. It has been relegated to the film industry, which has carried on the flame the last hundred years. Through film, classical music survives as a living tradition, but its new habitat comes with a downside: Over time, the orchestration has become poorer and there is increasing use of simple rhythms and digital sounds.

Where will classical music go if the orchestra hall, organic instruments and notation disappear, leaving the remains in the hands of digital gadgets? There are examples of interesting effects made in the synergy of computer programs and classical instruments. But when this intangible metaverse finally falls apart, the composer stands on bare ground. The belief in progress is one-eyed and ruthless towards the solid foundation that was built by our ancestors. Society is, so to speak, willing to throw away the foundation we stand on overboard in order to constantly find an easier way out.

With the accessibility and cost savings offered by digital tools, there is a risk that the orchestra hall will eventually disappear, along with the rich variety resulting from the human touch. Another problem is how the music is consumed. Here, too, accessibility is an issue. The new habit is to listen to music everywhere and at all times of the day. With wireless earplugs, people shut out the world, with the music’s only task being to dispel the silence.

The orchestra hall must carry the flame

Sleepy contemporary music and the worship of ashes in the orchestra hall seem to have ensured that an increasingly large part of the population has fled to popular music. The distinction between popular Hollywood and the snobbish orchestra hall has meant that the form of music has become either too simple or too «intellectual».

The orchestras must reintroduce the tradition of performing new tonal music, on an equal footing with the old. As our list shows, there is no shortage of talented composers who could turn the orchestra hall into a beacon for serious, modern music, as the cinema hall has been for the movies. A fifty-fifty rule for old and new works would be an incentive for composers to write more music in the classical spirit.

Honorable mentions:

Remo Giazotti

Adagio in G-minor (1958) Albinoni

Funeral services are probably well aware of this work, which can provoke tears faster than fresh scallions. It is probably perceived as more archaic than it actually is, because, against all presumptions, it was not written in the Baroque period. Remo Giazotti was a musicologist and helped to revitalize awareness of composers such as Antonio Vivaldi and Tomaso Albinoni. In his studies he supposedly discovered an incomplete work by Albinoni and published a finished version in 1958.

The original manuscript has never been shown publicly. Today, there is a consensus that such a manuscript does not exist and that Giazotti alone composed it.

Vladimir Vavilov

Ave Maria (1970)

This aria is not totally unknown to the modern Norwegian, but is he aware of how modern it really is? In fact, the work is not only new, but it has also been published under a false name. Because this piece really has nothing to do with the Italian Baroque composer Guilio Caccini. In reality, it was written by the Russian composer Vladimir Vavilov, who published it under Caccini's name due to the prohibition of religious music in the Soviet Union.

Vangelis

Mythodea: Music for the NASA Mission: 2001 Mars Odyssey (1993)

The Greek who died in 2022 is known for his use of synthesizers, but he deserves an honorable mention because his music was of such weight and expressive power that it would be a crime not to mention him.

Among individual concerts, his performance of Mythodea in Athens at the turn of the millennium stands as one of the most memorable concerts ever. The work, which amounts to a choral symphony, was performed by more than two hundred musicians, including the sopranos Jessye Norman and Kathleen Battle, as well as the composer himself at the keyboard. His attempt to recreate forgotten voices of Greek antiquity and join them with modern human hope and scientific achievement is an interesting project in itself.

With this almost otherworldly work, Vangelis shows that the "classical" does not necessarily have to be limited by form, technique and traditional instruments. Rather, it can spring directly from man's inner power, if one is able to find it.

(Copy edited by Joseph Leivdal)