Barbarism is the very symbol of chaos and destruction — resulting in the downfall of civilizations. Since the pinnacle of the Western civilization came hand-in-hand with the revival of classical painting and sculpture, perhaps the condition of these handcrafts are also indicative of the darkest times, which certainly might await us if we are not vigilant. But the important thing is not so much to explain why a culture gets enshrouded in darkness, but how some people carry the flame, leading people back into illumination. So what is the antidote to barbarism? Certainly not all the talented painters who are currently destroying their work in a muddled attempt to please the cult of invention. They, who knock desperately on the iron gates of the art world, ending their often anonymous careers somewhere in-between a 19th century academic painter and an infantile conceptualist.

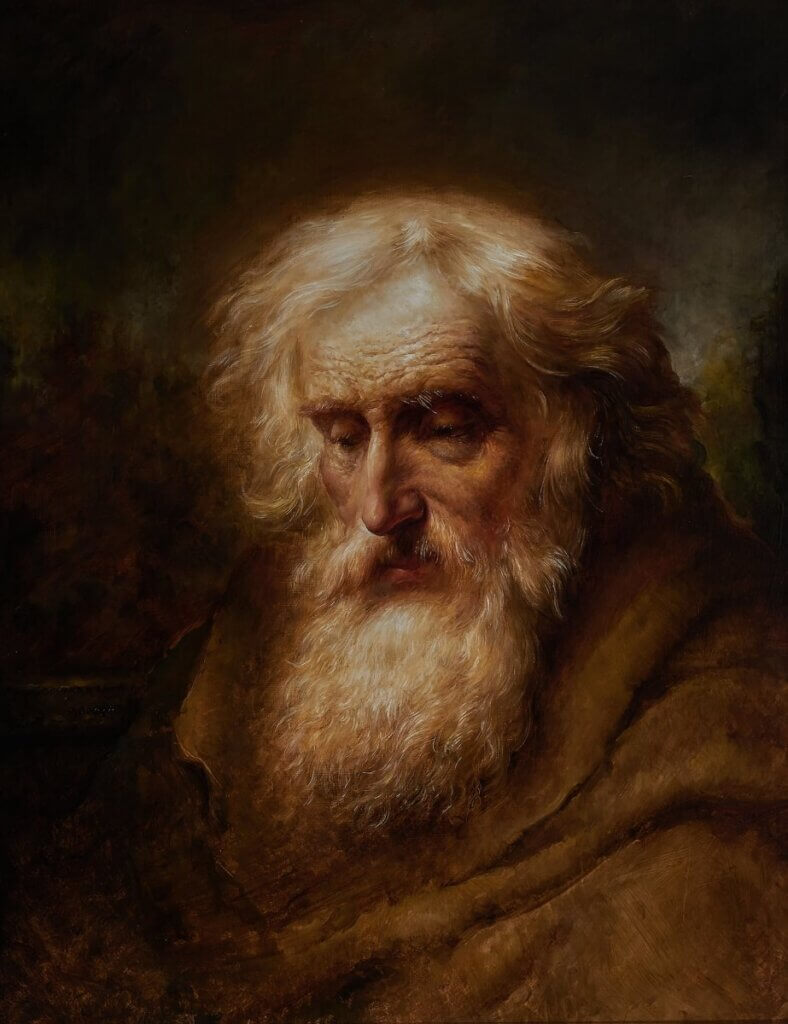

Those who understand the importance of a culture, seek its fountainhead. A living painter with this mindset is Marjan Bakhtiarikish. She looks to painters and paintings beyond the present (as well as the destructive tendencies throughout the 19th century), attempting to master that which was achieved by the giants of the Renaissance and Ancient Greece. Perhaps this is the reason why her rembrandtesque painting, “The Philosopher”, was awarded Jury’s Choice Award 1st place in the World Wide Kitsch Competition this year. Her painting was one of more than fifty, worthy finalists.

If we are lucky, and if the “pandemic” wills it, we will soon get to know her better — awaiting her anticipated appearance on The Cave of Apelles.

Ms. Bakhtiarikish, congratulations on your portrait winning the competition. What are your immediate thoughts?

– I am so deeply honoured by this precious award and recognition, it means a huge amount to me to be recognized by peers whose work I very much admire and learn from.

Your painting “The Philosopher” — what is it about?

– The painting came about as the result of a profound experience I had, standing for the first time in front of one of Rembrandt’s Tronies: “Bust of a Man in Oriental Dress”. It was three years ago during a Rembrandt – and Dutch Golden Age exhibition in Sydney. The painting was simply transfixing. The sense of heightened reality created by chiaroscuro, the texture of the painting, the subtle draughtsmanship, the total mastery of technique, all evoked a powerful human presence.

In the “Philosopher”, I wanted to take on the challenge of trying to evoke the same emotions Rembrandt’s painting communicated. I chose the character of an ancient philosopher to portray the sense of pathos and human dignity.

I felt the use of chiaroscuro was apt; the dramatic use of light could suggest the light of reason, while the enshrouding darkness suggested the questioning, self-doubt and weariness of life.

In a few words, what are you aiming at in your work?

– I aspire to recreate the same kinds of responses — emotional and intellectual — that I and many viewers experience in front of the great masterpieces of the classical past.

More than a naturalistic depiction

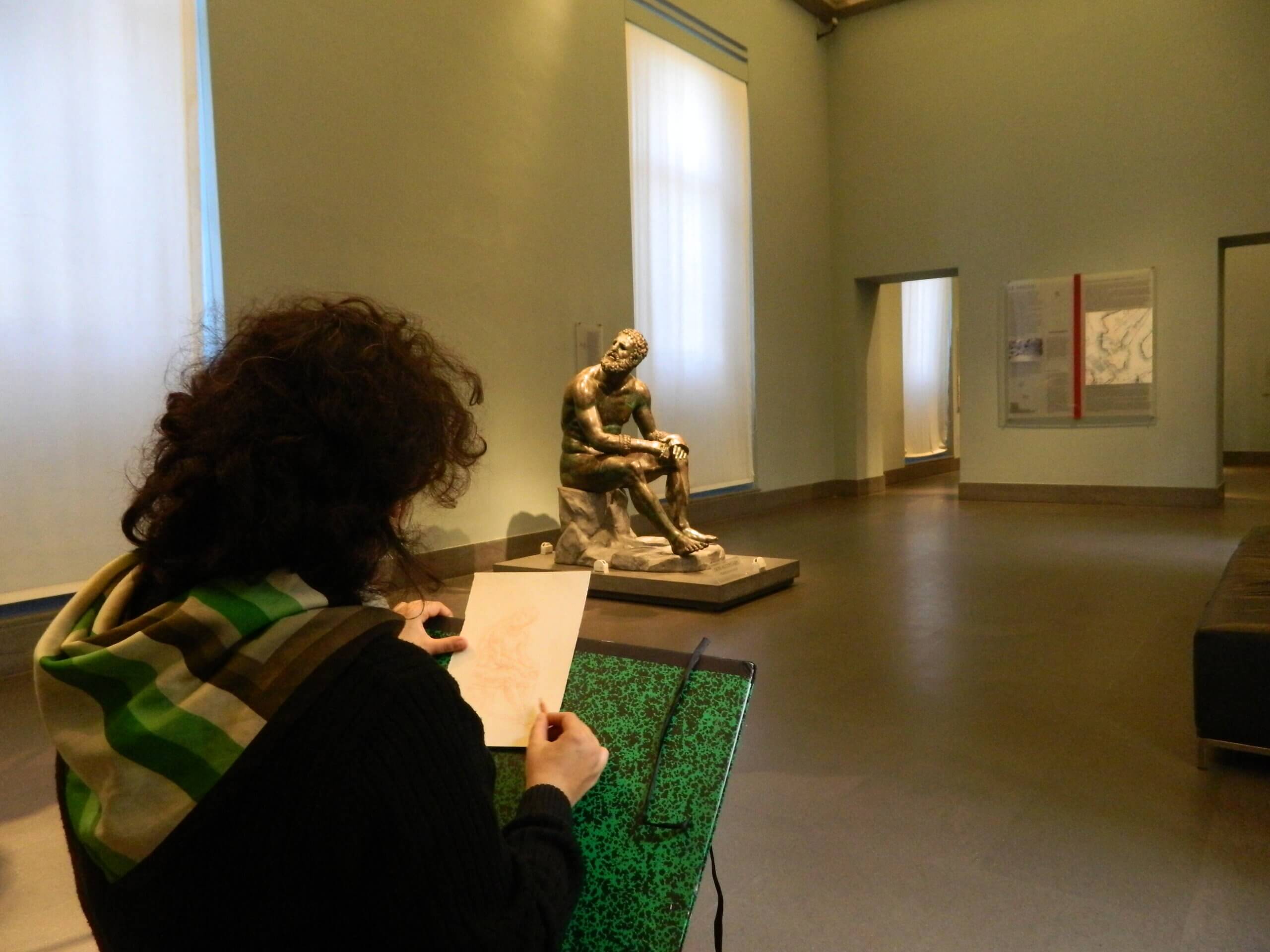

Marjan Bakhtiarikish studied for a short time with Charles H. Cecil in Florence, where she would also sit for hours on end, sketching in museums and galleries, including the Cabinet of drawing in the Uffizi. Doing this, she realized that the old masters combined realism with a powerful imagination and memory.

– Because of their constant reference to classical antiquity of idealized canons of the human figure and sense of beauty, the paintings would always be more than literal and naturalistic, she says, adding that she always follows the practice of working from copies of antique busts as per Rubens’ recommendation.

Relapse into barbarism

Marjan Bakhtiarikish says that her subsequent reading of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ lectures confirmed her commitment to studying and emulating the works of the old masters.

– Reynolds emphasized the importance of copying the Old Masters and imitating as many great painters of the past as you can, and not only that, but to go back to the “fountain-head”, which he believed to be “the monuments of pure antiquity”. Reynolds’ moving prophecy was that: “when the antiquity shall cease to be studied, we shall again relapse into barbarism”.

Do you see that “relapse into barbarism” happening today?

It seems to me that the traditions of the past are seen in a derogatory and dismissive way as something from a dead past that has no “relevance” today. The general attitude both in the wider culture and in the contemporary “art” scene seems to be that the only relevance of the classical past is to treat it with irony or denigration. Once you destroy and abandon the roots of this 2500 years of Western cultural heritage, then I do believe we are living in an age of “artistic” barbarism, where anything goes as long as it’s “new”, “original”, and “confronting”. I have seen the loss of these time-honoured values at least on the opera stages of many Western countries where the noble, intellectual and emotional intentions of the great classical composers are trampled on and ridiculed. This is why for me, it has been so heartening and elevating to have discovered the Kitsch movement and Odd Nerdrum, who try to uphold and emulate the values of classical painting that I admire and aspire to.

“Too Renaissance-like”

During the #kitschified campaign in February, Marjan Bakhtiarikish shared her story about how her professors had criticized her for being “too Renaissance-like” and that they urged her instead to “express herself”.

– As I have learned more about the Kitsch movement, I have come to realize that I have a lot in common, such as their emphasis on imitation rather than “artistic originality” as a path to true creativity, she says.

In line with the kitsch philosophy, Bakhtiarikish is not shameful, but proud of the fact that she is standing on the shoulders of giants. She enjoys all the classical disciplines, and says that she is particularly drawn to the heroic and monumental representation of the human figure. She lists poets like Milton, Shakespeare, Keats and Shelley among her literal influences. In music: Wagner, Bruckner, and Richard Strauss. In painting: Guercino, Rembrandt, and Watts.

– Among the living painters of today, I admire Charles H. Cecil. Apart from his rigorous and insightful teaching of painting from life, Charles had a large narrative painting (“The Deposition”) which had been in progress for more than twenty years. This commitment and practice was very inspiring to me.

In recent years I have discovered and studied in more depth Odd Nerdrum’s work as a rare example of true narrative painting today. His work has been a great influence in working towards finding my own approach to narrative painting.

Some would say that “my own approach to narrative painting” would be your “artistic originality”?

It’s a great question, and goes to the heart of the matter. For me, finding my approach to narrative painting in classical terms is quite the opposite of “artistic originality” as generally understood today. My aim as a classical painter is never to be “original”. As a classical painter (particularly today), it’s a challenge finding a path toward resolving one’s personal shortcomings (technical and intellectual) in order to produce a true masterwork. Working out one’s own approach simply means identifying those qualities lacking in one’s work which are present in Old Master paintings.

A condition of crisis for the Classical Tradition

Bakhtiarikish says that the situation for classical figurative painting in her home country, Australia, is in a condition of crisis, but not necessarily due to establishment-modernism.

– Although there has been a revival of realism, this has been mostly overwhelmed by photorealism and the “everyone is an artist” situation. Within Australia, however, there are individual painters who continue to work in sympathy with the Classical tradition, despite the difficult contemporary scenario.

How do we, and specifically painters, defeat a new darkening age of barbarism?

– In order to achieve the return to the “fountain head” in the way that the Renaissance painters did, in my view there are some real steps we can take. For me, this means developing an attitude of humility and self criticism in respect to the Old Masters. If it wasn’t beneath Michelangelo and other giants of the Renaissance to walk into the Brancacci Chapel to study Masaccio, surely it should be self-evident for us to do the same; similarly there is the example of Sir Joshua Reynolds, who had the humility to acknowledge at the end of his life that he wished he had studied Michelangelo more.

However an improvement in the technical aspect of painting is not enough; the mind of the painter needs to develop a classical taste through immersion in the best that Classical culture has offered including classical music, opera, literature and architecture, among others. As Leonardo advised in his Notebooks; if the painter does not have the “grace” and “beauty” within himself, he should find the best in nature and great masters to improve his mind. And the last important factor is that this is too much for an isolated individual to achieve and points to the importance of having the support of like-minded painters to create a community for competition, critique and mutual support. Through such a community the painters have a chance to re educate the public and to revive the value of the archetypal and timeless stories through narrative paintings.

The World Wide Kitsch Painting Competition is hosted annually, and takes place in November. Subscribe to The Kitsch Newsletter to receive updates about future competitions.