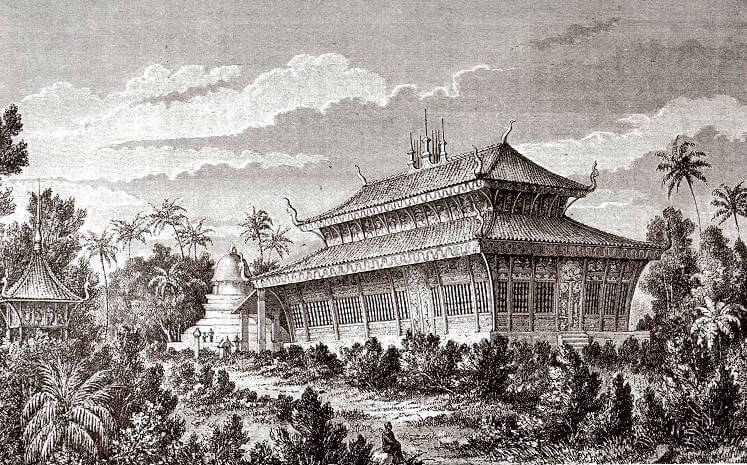

We are all aware of beauty. It is innate, natural and human. You see it in a child’s response to a butterfly’s wing. You hear it in the gasps of wonder as tourists turns the corner and stare at The Royal Crescent in Bath. It is ecumenical. From Luang Prabang in Laos to Siena in Italy, beautiful streets and buildings are not identical around the world. They vary with culture and climate. But they do rhyme. They have similar themes of colour, a strong sense of place, of variety in a pattern and of a coherent complexity of windows and doors in patterns with symmetry.

This is how we naturally build things, the timeless way of building, to cite the great Christopher Alexander. And you don’t need to come from a particular place to appreciate its qualities. This is why my eight-year-old son can arrive in Venice and stare up the beautiful palazzos from the Canal Grande. He has a look of infinite wonder in his eyes, even though he speaks no Italian and could tell you no more about the history of Venetian gothic, than he could about the far side of the moon.

We are all aware of beauty until we are taught, or teach ourselves, to ignore it. Too many of us are cast in mind-forged manacles. It is time to break free. And to create beauty for ourselves and demand it of our public bodies.

Why Beauty is Important

There are so many possible answers to that from the theological to the existential. I have one simple empirical one. Beauty matters because it is good for us. We know from several statistical ‘big-data’ analyses that when we spend time in places, we consider beautiful. We tend to be happier and healthier with less stress and lower blood pressure. We walk more in places we like. We know more of our neighbours. We are happier with our neighbourhoods. Surely that should be reason enough?

In policy circles talking of beauty, one risks embarrassment, says Dame Fiona Reynolds. Undoubtedly, a culture has evolved over the last 80 years, I know in Britain and I suspect more widely, of ignoring, even decrying beauty. In the worlds of politics, business and design, we do not consider beauty. We do not discuss it. We do not seek it. This is perverse and self-defeating.

Why We Have Forgotten Beauty

I believe that we have made this multi-generational error for two main reasons, each of them profoundly meretricious. First is the culture of naïve managerialism and overly confident economics. Those who run government departments or lecture in business schools believe that you should be able to measure and count everything.

But beauty is not of this nature. Like truth and goodness, it has an ultimate and foundational character. We pursue beauty because in doing so we are realizing our nature as free, self-conscious beings. And because the need to do this is so profoundly embedded in what we are, we can never find a definition of beauty that is not trivial or paradoxical. The question ‘what is beauty?’ is therefore no more susceptible of a straight and clarifying answer than the question ‘what is truth?’ However, our inability to answer that last question has never persuaded anyone that truth does not matter. Even if we cannot always fully agree about what we find beautiful the process of debating and discussing it will lift our collective sights and help us strive for better things.

The second reason that we have forgotten beauty is the long shadow of inhumane modernism. Egged on by the invention of the motor car, twentieth century planners and architects rejected the traditional town with its clear centre, composed facades, local materials, mix of uses and its walkable density. Streets, symmetry and coherent structure were all dissolved into a mush of hidden doorways, inhumane austerity of façade and unclearly public spaces. As Le Corbusier wrote: The street wears us out; it is altogether disgusting. Why, then, does it still exist?

The Lie

However, despite a hundred years of practice, the public continue consistently to reject this vision. The anonymous, featureless street-free neighbourhood of blocks in space is normally associated with higher crime, lower values and less neighbourliness. Many designers have in consequence fallen back on the lie that beauty is in the eye of the beholder and therefore should be ignored. What buildings look like, some argue, does not matter as it is all relative. I am sometimes tempted to respond to architects making this case to me, “If you really think that why not be an accountant?”

But more profoundly it is just not true. The polling, focus group, psychological and pricing data is consistent and compelling on the types of homes, places and town that most people want to live in and find attractive most of the time. At an individual level it may be hard to predict what any single person will or will not like. At the level of the wider population, it is remarkably easy. Simple clichés are dangerous things. And this one has probably done more harm than most.

Read Boys Smith’s article «The Values of Beauty» in Norwegian.

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founding Director of Create Streets, a social enterprise encouraging urban homes in terraced streets, not multi-storey buildings. He is co-chair, with Sir Roger Scruton, of the Building Better Building Beautiful Commission reporting to the Secretary of State for Housing. Nicholas is a member of the Historic England Commission, an Academician of the Academy of Urbanism and a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Buckingham.