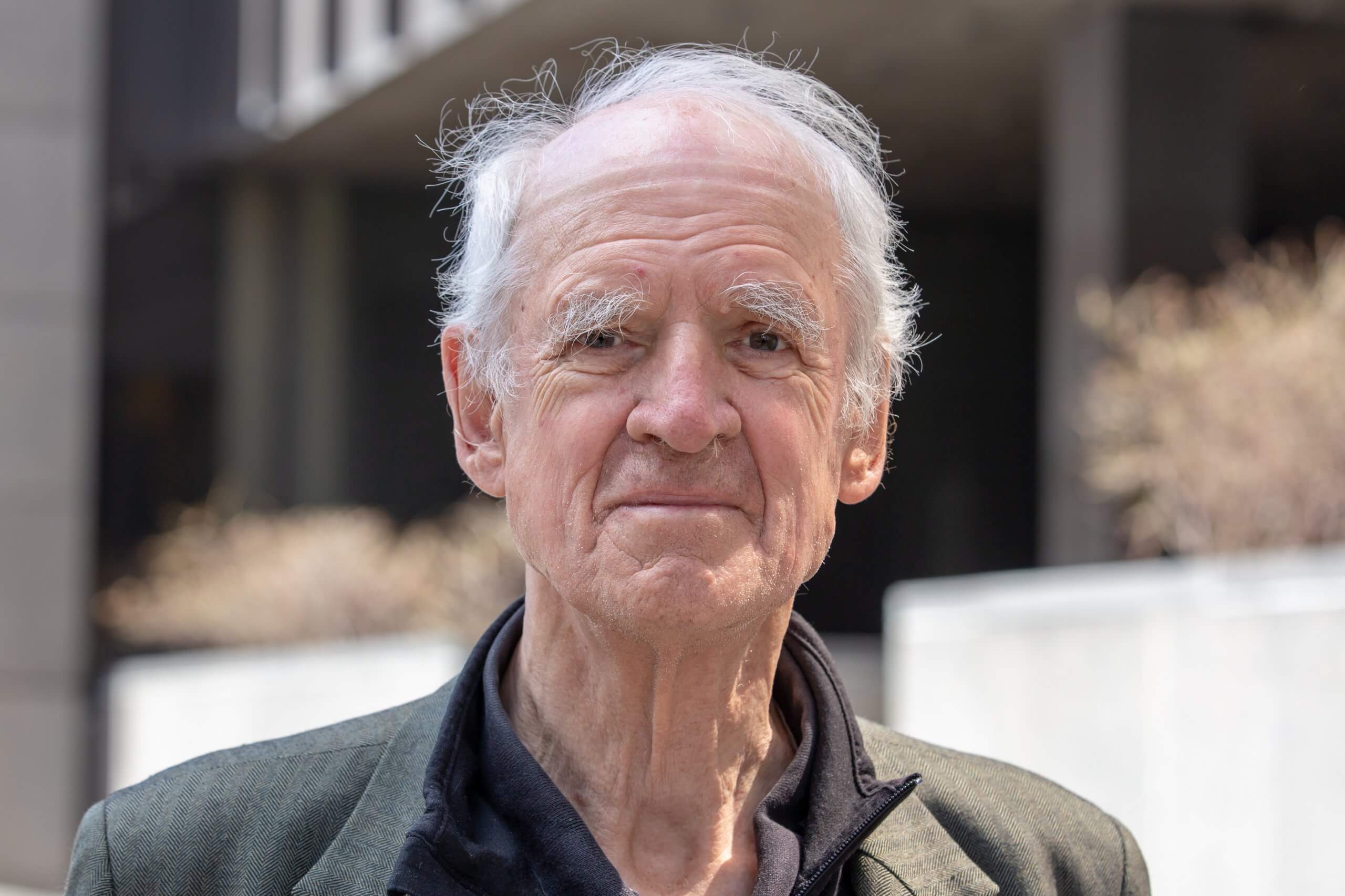

Classical architecture is not a left versus right issue, claims Justin Shubow, the President of the U.S. think tank National Civic Art Society (NCAS) and Chairman of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. Shubow has been a strong defender of the recently signed Executive Order “Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture.”

He strongly hopes that the Biden administration will not revoke the recently signed Executive Order on classical federal architecture, arguing that this is one aspect that unites an otherwise divided nation, pointing to a new survey by NCAS showing that 72 percent of Americans prefer traditional over modernist architecture for federal buildings.

– Architect organizations have criticized the Executive Order for tying classical architecture to one political side. What are your thoughts on that?

– I don’t believe that classical architecture is a partisan issue. When people see the U.S. Capitol or Supreme Court building, they don’t think “This is a Republican building or a Democrat building.” They just appreciate them for what they are, and for them such architecture is the architecture most connected to American democracy at its noblest. It is telling that after the riot at the Capitol, politicians of both parties deplored what they called the “desecration of the temple to democracy.” This terminology – the idea of the temple and of sacredness – is an effect of the building’s classical architecture.

According to Shubow, the fact that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a proponent of classical architecture shows that this is not a left versus right issue.

– President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a staunch defender of classical architecture in opposition to the modernists who, for instance, opposed the Jefferson Memorial. FDR had a strong hand in the design of Washington, D.C., and when Americans think of the federal buildings from the New Deal Era, they think of classical buildings. People have, I think, positive feelings towards that government architecture, he says.

Shubow adds that a giant Greek Doric stage was constructed as the backdrop for President Obama’s 2008 historic nomination acceptance speech.

– President Obama was associating himself with classical architecture, says Shubow.

Eliminating the Bias Against Classical Architecture

The National Civic Art Society was founded in 2002, and is headquartered in Washington, D.C. The organization gained much media attention through projects such as criticizing the proposed postmodernist design for the National Eisenhower Memorial, and the initiative of rebuilding the original Pennsylvania Station in New York, a Beaux-Arts design demolished in the 1960s that once was described as the most beautiful train station in the world. Lately, NCAS has been one of the main forces championing the recently signed Executive Order, arguing that it is important to eliminate the bias against classical architecture in federal government design.

– Do you think that President Biden will revoke the Executive Order?

Shubow points again to the aforementioned survey and the overwhelming preference for classical architecture within all demographic groups: age, gender, race, income, and even political party. On its website, the NCAS states that the survey was done by the Harris Poll, a reputable, non-partisan firm.

– Given the survey’s strong evidence that classical architecture is something that Americans would prefer, why would President Biden want to remove it?

– What would be the result if the Executive Order is not revoked by the Biden administration?

– If the Executive Order is kept in place, it will result in the government constructing significantly more classical and traditional buildings, and I think these buildings will be very successful with the American people.

During the current federal design program in the U.S., which began in 1994, there have been 78 new buildings and only six of them have been classical or traditional. According to Shubow, this is totally “out of whack” with what ordinary Americans want.

– It is important for people to understand that for a long time there has been very heavy modernist bias in federal design. The most important thing is to eliminate the bias against classical and traditional architecture, he says.

If the bias is eliminated and more classical buildings are being constructed, Shubow argues, the public will react positively.

– The public will realize that they don’t have to put up with the ugly, banal, or even bizarre federal buildings that they have been getting for decades and decades. So much of the built environment has been made a worse place by modernist architecture. Ordinary people don’t like it, and the architects themselves don’t really care what laypersons think.

Power to the People, Not the Architects

The Executive Order is meant to replace the existing Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture, which was a page inserted into an official report on government office space approved by President John F. Kennedy in 1964. It is the Guiding Principles that has resulted in what Shubow calls a “heavy bias against classical architecture.” Reading through the Guiding Principles, one can for instance read phrases stating that “contemporary American architectural thought” ought to be emphasized, as well as other principles that implicitly favor modernist design. However, since the E.O. was leaked, there has been arguments of which one is more restrictive – the E.O. or the Guiding Principles.

– Is the Executive Order more restrictive than the existing Guiding Principles? That has been some of the criticism of the E.O.

– The Guiding Principles that currently direct government architecture essentially ban classical architecture and favors modernism. In addition to that, they require that design should flow from the architectural profession to the government and not the other way around. So, they essentially abdicate responsibility from the government to the architectural profession. I think the profession’s preferences in architecture are extremely divergent from what ordinary Americans want, Shubow answers before adding:

– The Executive Order requires buildings to appeal to the American people. It is not about appealing to architects; it is about appealing to the true clients of these buildings. The order is highly democratic in the sense that it gives Americans what they want.

– The way I read the Executive Order, it removes authority from the architects when it comes to deciding how a federal building should be designed. Some call this undemocratic. However, an undercommunicated aspect of the Executive Order seems to be the fact that it moves some of that authority to the local public (See sec. 2d and 3e of the E.O.). That is, moving power from experts to the people.

– Indeed. Some critics of the Executive Order, such as the American Institute of Architects (AIA), argued that the order doesn’t give locals enough of a voice, when in fact the current system doesn’t give any voice to the people who live in the areas where these buildings are constructed. The new Executive Order does exactly that and adds an element of democracy into federal design.

– Why are organizations such as the Institute for Classical Architecture and Art (ICAA), whose purpose is to promote classical architecture, against the new Executive Order?

– I think that some of that comes from the fact that President Trump is, to put it mildly, a highly controversial figure. If this executive order was drafted by a President Biden, a President Clinton, or even a President Bush, the debate over it would not have been as explosive.

The Philosopher’s Arguments

Shubow’s reasons for promoting classical architecture are also of a philosophical nature. Having completed four years in the PhD program in Philosophy at University of Michigan, his background in philosophy is strong and promotes an investigative attitude towards complicated questions.

– In architectural debates, the issue of whether beauty is solely in the eye of the beholder is a common issue. You have previously stated that there are objective standards of beauty. What are some of these objective standards, and how do you go about to discover them?

– I do think there is a human nature, and that there is something within human beings generally that causes us to find certain things particularly beautiful. There are scientific studies of what in human beings we find beautiful. Even something as basic as bilateral symmetry is something that we find beautiful, Shubow explains and adds:

– It is not only that too many modern architects disagree with the layperson as to what is beautiful, in many cases beauty is not that important for them. They might think that beauty and all these similar terms represent antiquated bourgeois values. “If your grandma likes something, then it must be kitsch. We are not like that. We are far more sophisticated. We like minimalism. We like stark white rooms, exposed concrete walls, and harshness.”

At the extreme, Shubow argues, this attitude is a kind of nihilism. He quotes the deconstructivist philosopher Jacques Derrida, who said, “Architecture is the last fortress of metaphysics.”

– I think what Derrida meant by that is that architecture, in the traditional sense, gives us a sense that there really is the true, the beautiful, and the good existing out there. But Derrida, whom I view as a kind of radical relativist, wishes to destroy metaphysics as we know it, and therefore to destroy architecture.

That is arguably why some modernist buildings have unconventional designs, such as uneven floors, disoriented stairways, floors looking like they are flying in the air or roofs looking like they will cave in.

– It’s a rejection of the constitutive values of architecture as such, claims Shubow.

The Rejection of Zeitgeist

Shubow is obviously not in accordance with his time – at least not in a Hegelian sense. Instead of claiming that a building should “reflect its time,” he argues that it ought to serve the people it is made for.

– I do think that if you have a training in traditional philosophy, including Enlightenment philosophy, you can see a lot of the flaws in the philosophy underlying so much of modernist architecture. If you look at the great modernist thinkers, so many of them are steeped in Hegel, the 19th-century German philosopher. They have this sort of metaphysical belief in the progress of history, that history is unfolding in some particular way, and therefore buildings need to express the age.

As an example, he quotes the foundational modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who said: “Architecture is the will of the epoch translated into space.”

Shubow is rather a reader of philosophers such as Karl Popper, who was highly critical of what he called historicism. “Historicism” is the idea that there is determinism in history, that we can see the future, and therefore, we make judgments about how history is unfolding and how we ought to act.

– In my view, historicism is false, and therefore I think that so much of the philosophy underlying modernist architecture is also false. There is no such thing as the direction of history, there is no such thing as the Zeitgeist, Shubow claims and continues:

– Early modernist architects would claim that there are no aesthetic preferences on their part, but rather that the spirit of the age – which they assume to be a beneficial spirit – is only acting through them in some mystical way. To me, that is obviously false. Yet, so many architects believe architecture must follow the Zeitgeist. It’s not that they are consciously Hegelians. Most don’t know who he was; they don’t see the water in which they swim.

– What are your arguments for claiming that there does not exist a Spirit of our Age?

– Well, I do not believe that spirits exist in any metaphysical sense. Obviously, there are trends in any particular time, but here is no geist in the way Hegel used the term. Moreover, there are diverse trends—whether regarding economics, technology, politics, culture, and so on—many of them moving in different and contradictory directions. Some trends are good, others bad. There’s no end of history that we are heading towards, and there is no essence of our time, says Shubow before adding:

– When architects so frequently talk about needing to build for our time, the spirit of our time, do they really think theyare the one able to determine even what that Zeitgeist is, even assuming there is such a thing? Are they great thinkers?

Some of today’s architects attempt to follow the Spirit of the Age by rather simplistic reasoning, he argues. For instance, some architects design buildings that look “digital,” such as so-called Jenga Architecture, since we live in a digital age. Shubow argues that good architects need to be more sophisticated in the way of thinking if they are to make good buildings.

– If the world is changing so fast, it is reasonable to think that people are in greater need of a sense of comfort and security and a place of home. So, therefore, architecture should be more traditional and rooted when certain aspects of life are so liquid.

What Makes a Good Building

– What would you say are the basic criteria for a good building?

– I am heavily influenced by Vitruvius, the ancient Roman architect. He said that the three criteria for building are commodity, firmness, and delight, says Shubow.

He describes the three criteria: Commodity meaning that a building suits its purpose and function; Firmness meaning that a building is solid and appears solid; and Delight meaning that a building is beautiful and pleasing to the eye.

– When it comes to our evaluations of buildings, they are very much tied up with our concept of the embodied human self: Our particular dimensions and spatial orientation, our size, our need for safety and security. And these I think are very objective, argues Shubow.

People prefer the appearance of brick house in a storm than a straw house, he argues. At the same time, he continues, if a building is too large, or superdimensional, it might be overwhelming or causing feelings of fear, and that would be an unpleasant experience.

– Most of the time we want to be in places that are pleasing, comforting, and that gives us a feeling of security.